I never meant to find them. The old manila folder was wedged between my parents’ tax documents and a stack of expired insurance policies in the filing cabinet I was helping Mom organize. She’d asked me to sort through decades of paperwork while she recovered from knee surgery, and I’d agreed without hesitation. After all, I was the reliable one—the eldest daughter who always showed up when needed.

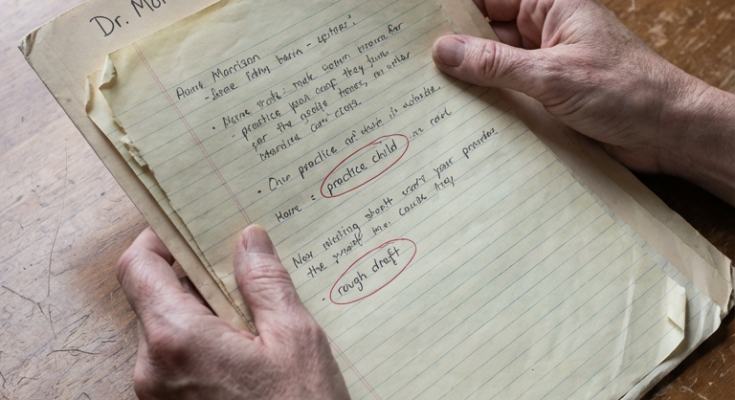

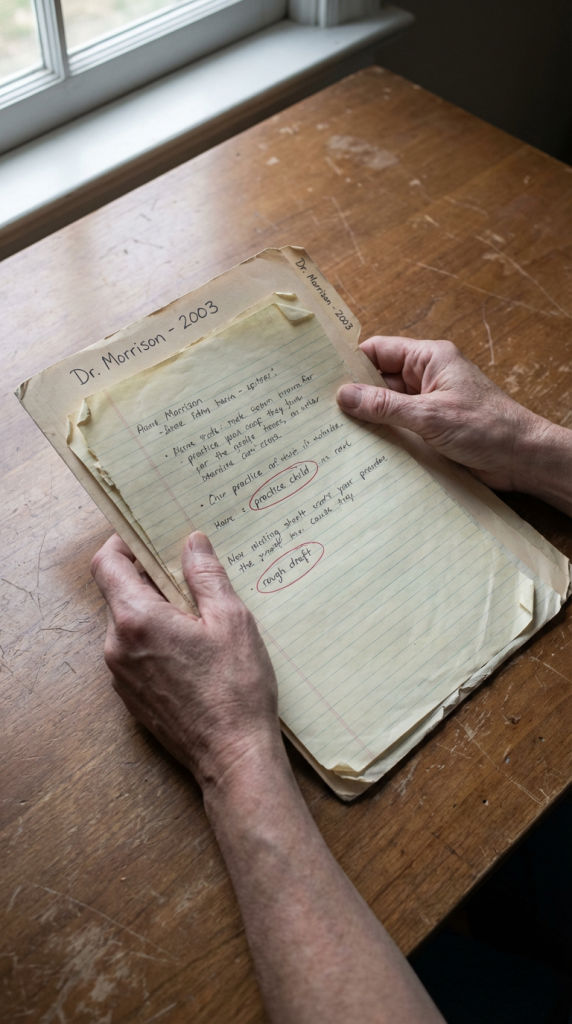

The tab read “Dr. Morrison – 2003” in my father’s neat handwriting. I almost tossed it in the shred pile without looking, but something made me pause. 2003. I would have been seven years old that year. My brother Jacob was four, and my sister Emma hadn’t been born yet.

I opened the folder.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

The first page was an intake form with both my parents’ signatures at the bottom. Presenting issues: “Communication breakdown, resentment about parenting approaches, considering separation.” My chest tightened. I’d never known they’d almost divorced. Our family photos from that year showed smiling faces at my second-grade graduation, a beach vacation, Sunday dinners with grandparents. No hint of the fractures beneath the surface.

But it was the session notes—handwritten, probably by my father who always took notes on everything—that made my hands start shaking.

Session 4, March 2003: “Discussed feelings about firstborn. Both agree parenting Sarah has been ‘learning experience’ with many mistakes. Dr. M suggests this is normal. Tension about different approaches with S versus J. Wife feels husband too critical of her parenting of S. Husband feels wife too permissive with J as ‘correction’ for being hard on S.”

Session 7, April 2003: “Made breakthrough about ‘practice child’ concept. Both acknowledged treating Sarah as ‘rough draft’ while figuring out parenting. Wife tearful admitting she wishes she could do Sarah’s early years over. Husband admits being overly strict with S in ways he regrets. Both agree they’re better parents to Jacob because of lessons learned. Dr. M. normalized this but encouraged addressing lingering guilt.”

Practice child. Rough draft.

I sat on the office floor, papers scattered around me, reading note after note that detailed my parents’ journey through marriage counseling. Most of it was about their communication issues, their different upbringings, their struggles with my mother’s demanding career and my father’s traditional expectations. But woven throughout were references to their parenting evolution—how they’d been too strict with me, too anxious, too controlling. How they’d relaxed with Jacob. How they planned to be even better parents if they had a third child.

Emma was born eighteen months later. The “intentional” baby, conceived after they’d “done the work” to save their marriage and become better parents.

The Pieces Started Falling Into Place

I didn’t confront them that day. Or the next. Instead, I went home to my apartment and started remembering. The memories came in fragments, puzzle pieces that suddenly formed a picture I’d never fully seen before.

The violin lessons I’d hated but was forced to continue for six years because “quitting isn’t an option, Sarah.” Jacob tried violin for four months before my parents let him switch to drums without a fight. “We want him to be passionate about his music,” Mom had said.

The strict 8 PM bedtime I’d had until fifth grade while Jacob got to stay up until 9 PM in second grade. “We were probably too rigid with you,” Dad had admitted once. “We’ve learned to be more flexible.”

The fact that I wasn’t allowed to watch TV on school nights, but by the time Emma was in elementary school, the whole family watched together most evenings. “House rules evolve,” Mom had said when I pointed it out during a college visit home.

The way they documented every milestone of my early years with anxiety-filled baby books—”Sarah walked at 11 months, 3 weeks, 2 days. Is this too early? Too late?”—while Jacob’s baby book had far fewer entries and Emma’s was mostly empty. “We were more relaxed by then,” they’d laughed. “We knew everything would be fine.”

Every explanation, every “we’ve learned” and “we’re more relaxed now” suddenly had new meaning. They weren’t just becoming more easygoing parents. They were actively correcting their mistakes with me by doing better with my siblings.

The Weight of Being the Experiment

I’m thirty now. I have a master’s degree, a good career, healthy relationships, and a therapy bill that’s taught me to process childhood experiences with nuance. I know my parents loved me. I know they did their best. I know that all first-time parents make mistakes and learn as they go.

But reading those notes awakened something I’d been pushing down for years: the feeling that I’d always been held to different standards, that rules applied to me that didn’t apply to my siblings, that my childhood was somehow less joyful and more regimented than theirs.

The notes mentioned specific examples I remembered vividly. The time I got a B in third-grade math and was grounded from playdates until I brought it up to an A. My father had written: “Realize in retrospect this was too harsh. Wouldn’t handle this way with J.” Jacob barely maintained a C average in high school, and my parents hired a tutor and told him “just try your best.”

The elaborate chore chart they’d created for me at age six, with consequences for incomplete tasks. “Too young for this responsibility level,” my mother had written in the notes. “Should have let her be a kid more.” Emma didn’t have regular chores until middle school.

The fact that I wasn’t allowed to date until I was seventeen, had a midnight curfew in college when I visited home, and was expected to call home three times a week my first year away. Jacob started dating at fifteen, had no curfew by sophomore year of college, and my parents were happy to hear from him weekly. “We were too controlling with Sarah,” the notes said. “Learning to trust more with J.”

Confronting the Truth

I kept the secret for two months before I couldn’t anymore. I was at Sunday dinner—still the reliable daughter who showed up every week—watching my parents laugh with Emma about some ridiculous TikTok trend, being the cool, laid-back parents I’d never known growing up.

“I found your marriage counseling notes,” I said into a sudden silence.

My mother’s face went white. My father set down his fork carefully. Jacob and Emma looked confused.

“Sarah,” Mom started, but I held up my hand.

“I know you almost got divorced when I was seven. I know you worked through it, and that’s great. I’m glad you stayed together.” I took a breath. “But I also know you called me your ‘practice child.’ Your rough draft.”

“That’s not—we didn’t mean—” Dad stammered.

“It’s in your handwriting, Dad. Multiple sessions about how you learned from your mistakes with me. How you were better parents to Jacob because you figured out what not to do with me first. How Emma was going to get the benefit of all that growth.”

Emma looked stricken. Jacob shifted uncomfortably. My parents looked at each other with that wordless communication that comes from decades together.

“You weren’t supposed to see those,” Mom whispered.

“Clearly.” I laughed, but it came out bitter. “Here’s what I’m struggling with. I don’t blame you for making mistakes with me. Every first-time parent does. But you knew you were doing it differently with them. You actively decided to give them easier childhoods than you gave me. And you never apologized. You never even told me.”

Their Side of the Story

What followed was the longest, most honest conversation we’d ever had as a family. My parents didn’t make excuses, but they did explain.

They’d been twenty-five and twenty-six when I was born, barely adults themselves. Both came from strict households and defaulted to what they knew. My father’s parents had been authoritarian; my mother’s had been anxiously overprotective. They’d combined the worst of both approaches without realizing it.

By the time Jacob came along, they’d spent three years making mistakes and seeing the results—a anxious, perfectionist daughter who was afraid to disappoint them. The marriage counseling had forced them to examine their parenting alongside their relationship issues. They’d read books, learned about child development, understood that their approach was creating more harm than help.

“We couldn’t go back and change how we’d parented you,” Mom said, tears streaming down her face. “We could only do better going forward. And we thought—we hoped—that doing better with Jacob and Emma would show you that we’d grown. That we’d learned.”

“But you never told me that I wasn’t the problem,” I said quietly. “Do you know how much of my childhood I spent thinking I was difficult? That I was the kid who needed all the rules and structure because something was wrong with me? Jacob got away with everything, and I thought it was because I’d used up all your patience.”

The silence that followed was crushing.

“You were never the problem,” Dad finally said. “We were. And I’m so sorry we never said that clearly.”

The Aftermath and What I Learned

That conversation happened three months ago. We’re in family therapy now—all five of us, plus Emma’s fiancé who wanted to understand the family dynamics. It’s awkward and painful and sometimes I want to skip sessions, but I show up. Because I’m still the reliable one, apparently, even when I’m working through being angry about how I became that way.

My siblings have been unexpectedly supportive. Jacob admitted he’d always felt guilty about getting away with things I’d been punished for. Emma confessed she’d noticed the different standards and wondered why. They’re both processing their own complicated feelings about being the “beneficiaries” of my parents’ growth.

My parents are trying. They’ve apologized more times than I can count. They’ve acknowledged specific moments where they were too hard on me, too demanding, too inflexible. They’ve told me they’re proud of who I became, but they wish they’d helped me enjoy the journey more. They’ve admitted that some of my anxiety and perfectionism likely stems from their early parenting.

Here’s what I’m learning: You can acknowledge that your parents did their best while also recognizing that their best hurt you. You can love them and be angry at them. You can appreciate who you’ve become while grieving who you might have been with a gentler childhood.

I’m also learning that being the oldest child—the “practice child”—is complicated in ways people don’t talk about enough. We’re the ones who get the strictest rules, the highest expectations, the least benefit of the doubt. We’re the ones our parents learn on. And while every family is different, there’s something universal in the experience of watching your younger siblings get the relaxed, evolved version of your parents that you never knew.

Moving Forward

I don’t know what complete healing looks like yet. Some days I’m fine, able to laugh about childhood stories without resentment. Other days I’m furious that I spent so much of my youth trying to be perfect for parents who were still figuring out how to be parents.

What I do know is that finding those notes, as painful as it was, gave me permission to stop gaslighting myself. All those times I thought “maybe I’m remembering wrong” or “I’m probably being too sensitive”—I wasn’t. The difference in how I was raised versus my siblings was real, documented, discussed in therapy sessions I knew nothing about.

I also know that I’m breaking the cycle. When I have kids someday, I’ll make mistakes too—different mistakes, probably, but mistakes nonetheless. The difference is that I’ll own them. I’ll apologize when I mess up. I’ll tell my firstborn that yes, I’m still learning, and I’m sorry they have to experience that learning curve. I’ll make sure all my children know that different doesn’t mean better or worse—it just means I grew.

And maybe most importantly, I’ll never, ever call any of them my “practice child” where they might find it someday.

Because here’s what I’ve learned: children aren’t rough drafts. They’re not experiments or trial runs for the siblings who come after. They’re whole people deserving of their parents’ best efforts in real-time, not in retrospect.

I was seven years old in those photos from 2003, smiling at my second-grade graduation while my parents sat in marriage counseling discussing their mistakes in raising me. I deserved better than to be their practice round. Every firstborn does.

But we survive it. We grow from it. And if we’re lucky—and do the work—we eventually find a way to forgive it while still holding space for the anger, the grief, and the knowledge that we deserved more.

I’m still figuring out which kind of lucky I am.